128 Days Later: The Marathon Truth – Running Isn’t the Hard Part

- Yeheshan de Silva

- Oct 18

- 6 min read

Today, as I reflect on crossing the finish line of the LSR Colombo Marathon, still unable to belive that I actually completed a Marathon; my body is recovering, and my heart is full! The euphoria of those final steps is real, yet it only lasted a few minutes. The true achievement, the real difficulty, lay in the 128 days that led up to it.

This is the central truth I learned: Running a marathon is not difficult; training for a marathon is.

The Beginning: A Plan and a Purpose

My journey started on June 1st, the day my 18-week training plan kicked off. The total commitment spanned 128 days, a period that demanded sacrifice, consistency, and a profound mental shift. My initial goal for Colombo was simple: finish. But I knew a solid plan was the only way to get there.

The training was strategically broken down into phases, starting with a base build. It was a monotonous, beautiful grind of easy runs, building my mileage from single digits up to the necessary weekly volume. The early mornings, the late evenings, the constant laundry pile of sweaty running gear—that was the daily reality.

Side Note : The training plan was crafted by “Chat GPT”, and I had it reviewed by Coach Tharindu from my Colombo Night Run Family.

The Mid-Point Test: Chasing Speed at Arugam Bay

Midway through the plan, on August 10th, I had a crucial milestone: the Arugam Bay Half Marathon. This wasn’t just a fun run; it was a targeted test of fitness and speed. The first half of my training plan was deliberately structured to push my pace, preparing me to aim for a sub-2 hour finish.

The intense speed work, the challenging tempo runs—those are what sharpened my edge. On race day, I fought hard for that barrier, but finished in 2 hours and 6 minutes. While the two-hour mark remains for another day, this result was a massive personal victory: I crushed my previous personal best by nearly 8 minutes. The race served its purpose, confirming my dramatically improved speed and providing the perfect validation that the foundation was strong enough to pivot to the next, much more demanding, phase.

The Grind: Building the Endurance Beast

After Arugam Bay, the focus shifted entirely. The speed work took a backseat to the sheer volume of the Long Slow Run (LSR). This is where the real sacrifice—and the mental battlefield—kicked in. The training plan demanded I push the distance further and further: 25 km, 28 km, and finally the critical peak runs over 30 km. These runs are a world away from a 10K.

To prepare for the notorious heat of the LSR course, heat training became mandatory. It meant sometimes deliberately running when the sun was high, but mostly, it was about getting out the door before dawn to complete the mammoth efforts before the tropical heat became unbearable. Waking up at 4:30 AM on a Sunday to get a 3-hour run in was the norm.

The mental test peaked with my longest run: 33 kilometers executed entirely on the lane where my house is situated. The lane is just 250 meters long, meaning a full up-and-back loop was 500 meters. To hit 33 km, I had to run 66 loops. This repetitive monotony demanded an extreme level of mental fortitude. To pass the hours, I traded music for audiobooks and ran most of that morning listening to the gothic horror of Dracula. The sheer absurdity of running circles for hours while listening to a vampire story perfectly captured the surreal commitment of marathon training.

The Unexpected Hurdle: A Medical Scare

If the 128 days of training weren’t challenging enough, the final week threw an unexpected and terrifying curveball.

The Colombo Marathon, like many major events in Sri Lanka, required all athletes to undergo a mandatory Pre-Participation Medical Evaluation (Sports Medical Pre-Participation Evaluation). This isn’t just a quick check; it’s a vital step to ensure we’re fit enough to safely attempt the distance.

During my evaluation, the doctor performed an ECG (Electrocardiogram) along with other checks. My results flagged something concerning: a T-wave inversion in leads L3 and V1. For those unfamiliar, a T-wave inversion can sometimes be a sign of underlying heart issues.

Suddenly, my focus shifted from carbohydrate loading to cardiac health. The doctor, exercising the proper caution, paused my clearance and urgently requested an Exercise ECG (Stress Test).

The thought of failing the Pre-Participation Evaluation—of 128 days of sacrifice ending not with a finish line, but with a disqualification—was crushing. I spent the final, crucial days of my taper securing the stress test, running on a treadmill with electrodes attached, praying for a normal result.

Thankfully, the Exercise ECG came back clear. The anomaly was benign, likely a variation common in highly trained athletes. The doctor signed off, but the episode was a stark reminder: you can train your legs and lungs, but you must respect the engine that powers it all. Clearing that final medical hurdle added a new layer of gratitude and intensity to the start line.

Race Day: The Victory Lap

When I finally stood on the starting line in Colombo on October 5th, I was calm. The distance of 42.2 kilometers was intimidating, but I knew I had already covered that distance, and more, in training. The hard part—the 128 days of lonely commitment—was essentially over. The marathon itself was the final exam.

I started with a good rhythm, fueled by the energy of the crowd and the relief of the taper. I passed the half marathon mark at roughly 2 hours and 22 minutes, a solid, manageable pace that suggested a strong finish was possible. But the tropics have a way of humbling even the best intentions.

Around the 28-kilometer mark, the relentless morning heat took a heavy, physical toll. My pace cratered, and the remaining kilometers became a painful exercise in survival. This is where the race truly demands resilience, and where the training demands character—not just my own, but that of my crew.

I was incredibly lucky, because the mental fortitude I built was constantly reinforced by my support vehicle: my wife, mother, father, and my kids. They stuck with me, popping up along the course, their energy a lifeline when my own tank was empty. Beyond my immediate family, I had the incredible lift from my extended running family in the Colombo Night Run and Colombo City Running clubs, along with cheering strangers supporting other runners.

Every shout, every bottle of water passed, was a shared victory.

The final steps were a blur, fueled by pure stubbornness and the faces of those who believed in me. I owe a special debt of thanks to my good friend Heshan, who joined me for the grueling final 7 km. His company and unwavering motivation were the definitive push that kept me moving when my tank was completely empty.

The Numbers Game: Proof of the Grind

If the stories don’t convince you that training is the hard part, the numbers will. Looking back at the 128 days of the training plan, the statistics offer a raw, honest look at the commitment required. The goal wasn’t just to complete the marathon; it was to complete the plan.

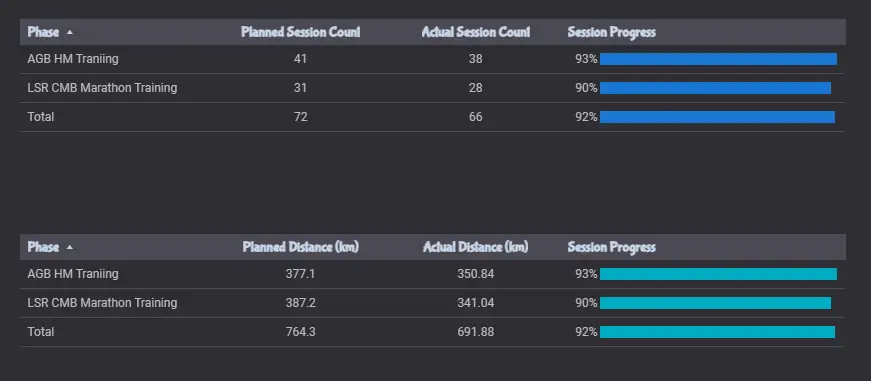

Here is the breakdown of the planned versus the executed volume (and training sessions):

To run almost 700 kilometers over a span of 128 days is a commitment that completely reshapes your life. Every single kilometer executed was a choice to prioritize the goal over comfort, fatigue, or social life. When you commit this much to a plan, the marathon becomes the validation, not the challenge.

To Anyone Considering the Challenge

If you want to run a marathon, you can. Your body is capable. But be prepared to commit to the process. The medal is the reward for enduring the 128 days of sacrifice—the missed sleep, the early alarms, the disciplined diet, and the sheer volume of kilometers logged.

The marathon finish line is the celebration. The training is the journey that changes you. I am eternally grateful for the structure and focus that the plan provided. It didn’t just get me across the finish line; it proved what I could achieve when I committed to a goal, day in and day out, for 128 days.

Comments